-

play_arrow

Like It A Lot Radio Todays Hits and Modern Electronica

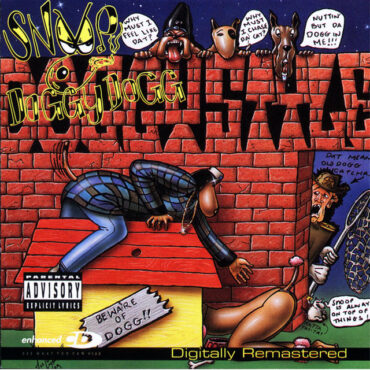

MOBY

PORCELAIN

Play is the fifth studio album by American electronic musician Moby. It was released on May 17, 1999, through Mute Records internationally and V2 Records in North America. Recording of the album began in mid-1997, following the release of Moby’s fourth album, Animal Rights (1996), which deviated from his electronica style; Moby’s goal for Play was to return to this style of music, blending downtempo with blues and roots music samples. Originally intended to be his final record, the album was recorded at Moby’s home studio in Manhattan, New York.

While some of Moby’s earlier work had garnered critical and commercial success within the electronic dance music scene, Play was both a critical success and a commercial phenomenon. Initially issued to lackluster sales, it topped numerous album charts months after its release and was certified platinum in more than 20 countries. The album introduced Moby to a worldwide mainstream audience, not only through a large number of hit singles that helped the album to dominate worldwide charts for two years, but also through unprecedented licensing of its songs in films, television shows, and commercials. Play eventually became the biggest-selling electronica album of all time, with over 12 million copies sold worldwide.

Track information

- Released April 25, 2000

- Studio Moby’s home studio (Manhattan, New York)

- Genre Downtempo

- Label

MuteV2 - Songwriter(s) Moby

Background

The second half of the 1990s saw Moby in career turmoil after years of success in the techno scene. The release in 1996 of Animal Rights, a dark, eclectic, guitar-fueled record built around the punk and metal records that he loved as a teenager, proved a critical and commercial disaster that left him contemplating quitting music altogether. He explained: “I was opening for Soundgarden and getting shit thrown at me every night onstage. I did my own tour and was playing to roughly fifty people a night.” However, positive reactions to Animal Rights from fellow artists such as Terence Trent D’Arby, Axl Rose, and Bono inspired Moby to continue producing music.

Moby started work on Play in August 1997 and put it on hold several times to complete touring obligations. At the time, he planned on making the album his last before ending his career. Recording sessions took place at Moby’s Mott Street home studio in Manhattan, New York. Play was delayed due to Moby’s dissatisfaction with the initial mix of the album that he had produced at home. A second mixing was completed at an outside studio before attempts at two other studios displayed similar results. After returning home and producing a mix by himself, Moby felt happy with it. Ultimately, he said that he “wasted a lot of time and money” on the previous unsatisfactory mixing sessions. Moby recalled a moment from March 1999, after Play had been mixed and sequenced, where he sat on the grass in Sara Delano Roosevelt Park: “I was sitting by the little tire swings that had been chewed apart by the pit bulls […] thinking to myself, ‘When this record comes out, it will be the end of my career. I should start thinking about what else I can do.'” At that point, he considered returning to school to study architecture.

When Moby finished recording Play, there was no sign that the album would perform any differently than Animal Rights. While he remained signed to the label Mute, which issued his records in the United Kingdom, Elektra had dropped him from its roster of artists following the release of Animal Rights, leaving him without an outlet to release Play in the United States. According to Moby, he shopped the record to every major label, from Warner Bros. to Sony to RCA, and was rejected every time. After V2 finally picked it up, his publicist sent the record to journalists, many of whom declined to listen to it. Moby’s manager Eric Härle said that their original goal was to sell 250,000 copies, which was what Everything Is Wrong (1995), Moby’s biggest-selling album at the time, had sold.

Critical reception

Play received widespread critical acclaim upon release. On Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating to reviews from mainstream critics, the album has a score of 84 out of 100 based on 20 reviews, indicating “universal acclaim”.

Reviewing for The Village Voice in 1999, Robert Christgau said the album’s sampled recordings would not “shout anywhere near as loud and clear” without Moby’s “ministrations—his grooves, his pacing, his textures, his harmonies, sometimes his tunes, and mostly his grooves, which honor not just dance music but the entire rock tradition it’s part of. He deemed the album “no more focused” than Moby’s previous “brilliant messes” but still “one of those records whose drive to beauty should move anybody who just likes, well, music itself. In his review for AllMusic, John Bush stated that Play showed Moby “balancing his sublime early sound with the breakbeat techno evolution of the ’90s. Barry Walters from Rolling Stone said “the ebb and flow of eighteen concise, contrasting cuts writes a story about Moby’s beautifully conflicted interior world while giving the outside planet beats and tunes on which to groove. David Browne, writing in Entertainment Weekly, felt that despite some needed editing, Moby’s graceful soundscapes filter out the original recordings’ antiquated sound and “make the singers’ heartache and hope seem fresh again. In a more critical appraisal, Pitchfork reviewer Brent DiCrescenzo believed the “raw magnetism” of the sampled recordings was lost to “innate digital recording techniques”, resulting in music that was “fun and functional, yet disposable.

At the end of 1999, Play was voted the year’s best album in the Pazz & Jop, an annual poll of American critics published in The Village Voice. Christgau, the poll’s supervisor, ranked it second best on his own year-end list. The following year, the album was nominated for Best Alternative Music Performance at the 42nd Grammy Awards. Since then, it has frequently been named one of the greatest albums of all time; according to Acclaimed Music, it is the 340th most ranked record on critics’ all-time lists. NPR named Play one of the 300 most important American records of the 20th century, as determined by the network’s news and cultural programming staff, prominent critics, and scholars. It was ranked number 341 on the 2003 and 2012 editions of Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, and in 2005, a panel of recording industry pundits assembled by Channel 4 voted Play the 63rd-best album ever. The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.

DID YOU KNOW?

Moby told Billboard magazine in 2000 that “Porcelain” was inspired by an ill-fated romance. “I was involved with this really, really wonderful woman, and I loved her very much,” he explained. “But I knew deep in my heart of hearts that we had no business being romantically involved. So, it’s sort of about being in love with someone but knowing you shouldn’t be with them.”

The track featured Moby’s vocals backed by a sample of vocalist Pilar Basso.

The song’s popularity was enhanced by being featured on the soundtrack of the 2000 movie The Beach and in the UK it became Moby’s highest charted song to date. Moby recalled to Rolling Stone: “Strangely enough, that’s probably the most signature song on the record, and I actually had to be talked into including it. When I first recorded it, I thought it was average. I didn’t like the way I produced it, I thought it sounded mushy, I thought my vocals sounded really weak. I couldn’t imagine anyone else wanting to listen to it. When the tour for Play started, ‘Porcelain’ was the song during the set where most people would get a drink. But then Danny Boyle put it in the movie The Beach with Leo DiCaprio. It was Leo DiCaprio’s first film since Titanic and everyone went to go see it. He used the music so well in the movie. I think that’s when a lot of people became aware of the record.”

This was released as the sixth single from Play. In the US, it peaked at #14 on the Dance Club Songs chart. One of six (out of eight) singles from the album to land in the Top 40 of the UK Singles chart, it fared the best, peaking at #5.

Moby also told Billboard he thought the delicate, melodic track was a nice contrast to some of the more aggressive tunes assaulting modern rock airwaves at the dawn of the new millennium. “I think that diversity is a very healthy quality when it comes to programming,” he said. “I’m certainly not criticizing modern rock radio, but it does seem like a lot of stuff that I hear does sort of sound the same. A lot of it is angry white guys who have listened to a lot of Limp Bizkit records. I would love to see a return to perhaps some of the more adventurous, open-minded formatting and programming that I grew up with in the ’70s and ’80s.”

EXPLORE OUR MUSIC

Copyright 2022. Ear Candy